Poland and Palestine after WWII: A Comparison

My wife and I were talking about it this evening, how her paternal ancestry was rooted in a part of Poland that doesn't exist anymore. The land exists, and many of the villages exist, but it stopped being Poland in 1945. Today it is part of Ukraine. We discussed how this might be similar to what happened around the same time with Palestine in the Middle East.

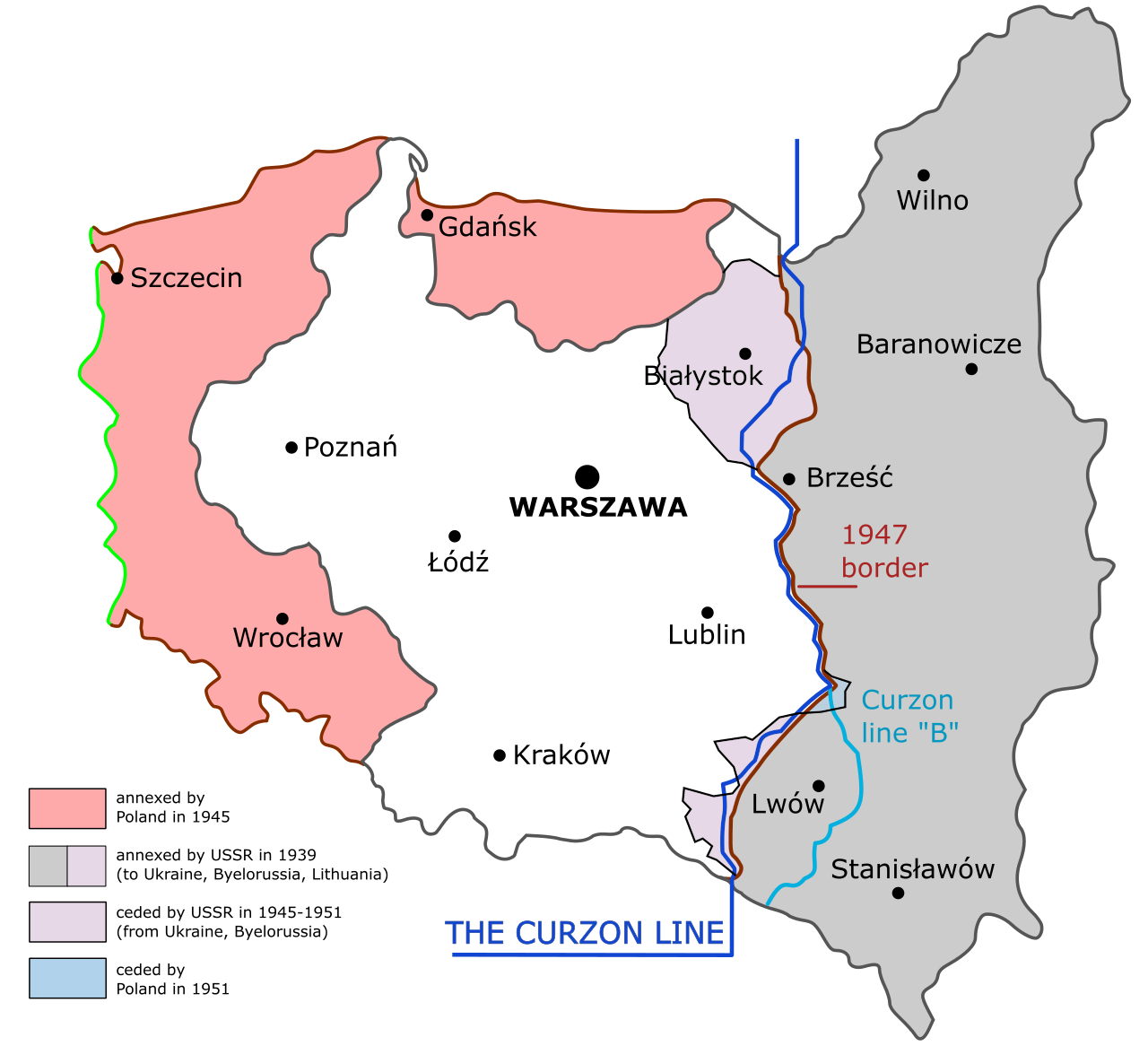

After WWII, Britain and the Soviet Union negotiated new Polish borders. On the one hand, northeastern Germany was absorbed by Poland. (That's why the city we live in now is called Szczecin, and not Stettin, and why Danzig is now Gdańsk.) On the other hand, eastern Poland went to the Soviet Union. Over one million Poles were forced to relocate. Looking at the map below (Poland gained the brightly coloured areas and lost the grey area), it's easy to see that Poland also got smaller in the process.

|

| Poland's borders before and after WWII |

This was only about two years before Britain abandoned its Palestine Mandate, leaving Israel with unstable borders and hostile neighbors.

After the Great War (the First World War), the League of Nations awarded Britain and France mandates for what had been the Ottoman Empire. There was no state of Palestine (or Jordan or Iraq or Egypt, for that matter) before WWI. There was the Ottoman Empire, and it was Muslim ruled. The majority of the population was Arab. There were Jews, too, and they had rights--sometimes more, sometimes less, but they were never equals. Towards the end of the 19th century, Palestine became more attractive to both Jews and Arabs. For Jews (partly because they were being forced out of other parts of the world) there was a growing desire to establish a Jewish state--or, if not a state, at least a homeland, preferably in their historic homeland. Jews had been living there for thousands of years, after all--since before Islam was founded and even before the Arabic language was born.

Very early in the 20th century, prior to the Great War, Palestinian Arabs had already begun to worry about the emergence of a Jewish quasi-state in Palestine. Even though it was still part of the Ottoman Empire, it was clear to Arab notables (including Christian Arabs) that new Jewish settlers had nationalistic aims. Thus there was organized physical violence against Jewish settlements in the region as early as 1914. This was before Zionism had gained significant support from Britain and, again, while Palestine was still part of the Ottoman Empire. It's worth emphasizing that the Zionist aims at this point were not specifically about the formation of a state, but more about the formation of a national home for Jews. However, even this relatively modest aim was not acceptable to the majority of Palestinian Arabs, and led to violence.

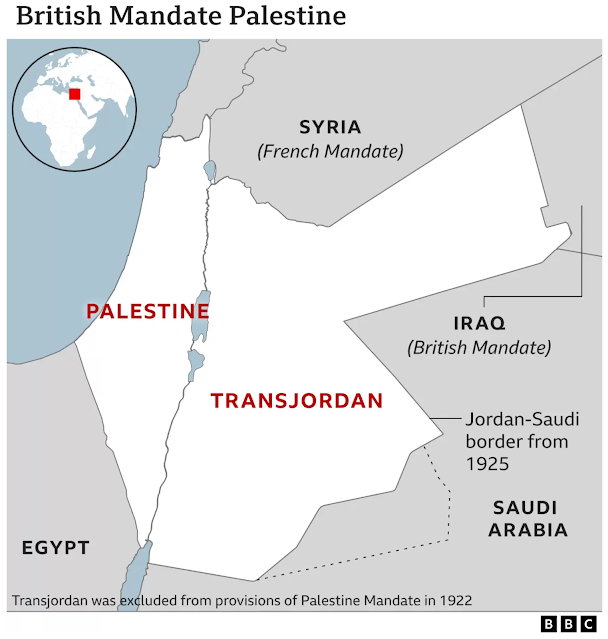

Britain did not know or did not care that the majority of indigenous Arabs (mostly, but not only, Muslim) did not want a Jewish homeland, let alone a Jewish state, in the region. The British thought that Arab nationalism and Zionism were compatible. Thus, in accordance with the Balfour Declaration of 1917, Great Britain was given a mandate for Palestine and Transjordan. This required the creation of national homes for both Jews and Muslims. The land west of the river was therefore to become a Britain-friendly Jewish state, probably because Britain wanted to maintain its trade route and keep Palestine out of French or Russian hands.

The land east of the Jordan River quickly became the Muslim nation of Transjordan (eventually Jordan), but the plan for Palestine was not so easily settled. The indigenous population and the international community could not agree on Britain's plan for Palestine. Eventually, the UN approved a two-state solution for the land west of the Jordan. To allow international control of the region, Jerusalem was to be an international zone.

Looking at the UN partition plan above, it's easy to see why Israel would feel unsafe and unsatisfied with the UN's borders. Not only would a hostile state stand between Jews and Jerusalem, but more threateningly, the southern part of Israel could easily be cut off from the north. Anticipating the coming Arab war, Israeli militias forcibly removed many Arab communities in that region (communities which were not a threat to Israel's military presence were allowed to stay). The displacement continued throughout the Arab-Israel war, on both sides of the Israel/Palestine border. Finally, and on its own, Israel successfully defended itself against Lebanon, Syria, Transjordan, Egypt, Syria, Yemen and Iraq, and thereby established new, more secure borders (also establishing unimpeded access to Jerusalem).

Even though the war ended and two Palestinian territories (what we now call Gaza and the West Bank) were in Arab hands, a Palestinian state was not established. Gaza became part of Egypt and the West Bank became part of Jordan. (That's why it is called the West Bank: It was the part of Jordan that lay west of the Jordan River.)With all of that in mind, I wonder what the exodus could have meant for most of those 700,000 Palestinian Arabs. Prior to the fall of the Ottoman Empire, Arab Muslims moved relatively freely from one territory to another. In so doing, some may have been leaving their tribes or sects, but they were not leaving their nation or their country. They were not even leaving Palestine (which was not yet a nation or a country, but only a territory). On top of that, many Arabs in Palestine had not been there for very long--perhaps only one or two generations. So why should they have felt that leaving one part of Palestine for another was such a catastrophe? How was it different from other migrations within the region during the reign of the Ottoman Empire?

The only significant difference, perhaps, was that Israel had become a Jewish state. Maybe it wasn't moving to Egypt and Jordan that was the problem. Maybe it was being displaced by Jews.

I do not mean to underplay the trauma that any mass displacement can cause people. Certainly many Palestinian Arabs felt a connection to the land that they left behind. However, Arabs being exiled from Israel was not comparable to Jews escaping massacred by Nazis in Europe. What the dislocated Arabs experienced was much more like what happened to Poles and Germans in 1945.

Palestinians in Gaza were not afforded all of the rights that other Arabs enjoyed in Egypt, but they were generally free and respected. Some even went to university in Cairo. Meanwhile, Palestinians in the West Bank were given full rights as citizens of Jordan. This may also help account for why there was no significant movement for a Palestinian nation at that time. There was absolutely a feeling throughout the Arab world that Israel should not be there, that all of the land west of the Jordan should be Arab, without any significant Jewish homeland at all. There was anger and resentment, but there was no organized movement of or for a Palestinian nation as such. At least, not in 1949.

I asked my wife, why didn't her grandparents want to reclaim the land that is now Ukraine? Their dislocation was surely just as traumatic, if not more so. For one thing, it came right on the heels of a Ukrainian massacre of between 50,000 and 100,000 Poles in German-occupied Poland during WWII. The horrifying details of this genocide are depicted in the phenomenal 2016 film, "Wołyń," which I only recommend if you have an iron stomach. (My wife's grandmother, who lived through the massacre, saw the film and said the reality was far worse!) Poles must have had very strong feelings about being forced off that land. To make matters worse, families were torn apart. Despite the tragic tensions between Poles and Ukrainians, there had been much intermarriage between them, which meant my wife's family and many others were forced to leave behind family members who weren't Polish. And yett, there has never been a movement to return, or to change Poland's borders to what they were before the war. More than that, Poland now supports Ukrainian independence.

After WWII, Arabs and Poles were similarly forced from their homes and had to relocate, though all remained in lands that were connected to their national and cultural identity. None had been forced to leave their own country or their own nation—though Poles were uniquely forced to leave their families. All were traumatised, but I'm tempted to say that Poles had it worse. Palestinian Arabs were free citizens living in Muslim countries in Palestine, whereas Poles were living behind the Iron Curtain, under constant watch and threat from the Soviet Union. Their identity was largely suppressed, and that could not be said of the displaced Arabs.

It is common these days to hear people say that Palestinians have been living under Israeli occupation for something like 75 years. Unless you count the existence of Israel itself as an occupying presence (which would be weird, since there was no country there for Israel to occupy), that is simply not true. It wasn't until the late 1960s that the territories of Gaza and the West Bank came under Israeli occupation, in response to yet another war started by Israel's neighbors (materially supported and motivated, if not entirely manipulated, by the Soviet Union). The West Bank has been occupied since then--about 55 years. Many would not say that Gaza has been occupied that whole time, however, since Israel completely withdrew from there in 2005. Furthermore, considering Gaza and the West Bank were never independent territories and had never established any sort of self-governance, I am not convinced that Israel was occupying either territory at all--at least not before the UN declared Palestine a state in 1988 (thanks largely to the Soviet Union's support of the PLO). Palestine's status as a state is still controversial, however, and Israel's rights with respect to those territories is still hotly debated.

After the Six Day War in 1967, I don't think Israel had a choice but to occupy Gaza and the West Bank, and I can understand why Israel's leaders continued to feel a need to occupy and promote settlements in them as a matter of national security. Obviously not all Israelis feel that way, and most of the rest of the world certainly doesn't feel that way. And perhaps I wouldn't feel that way, either, if Israel's neighbors were not a constant mortal threat.

I do not think nationalism is necessarily a problem, though it has played a problematic role in what has transpired in the Middle East. The political push for Palestinian national independence began in the 1950s in Cairo, by Palestinian refugees and also, notably, Yasser Arafat, a native of Cairo. The movement was explicitly aimed at reclaiming all of Palestine from Israel, but it did not gain broad traction until after 1967--after Israel occupied those territories and a great deal of anti-Israel (and anti-USA) antisemitic propaganda flooded the Middle East (thanks again to the Soviet Union). It took twenty-one years after Israeli occupation for a Palestinian State to emerge and be recognised at all. This was under the leadership of the Soviet-backed PLO, a designated terrorist organization. The two decades between 1967 and 1988 saw the simultaneous births of the Palestinian nation and systematic aviation terrorism, and both were orchestrated by the Soviet Union and the PLO.

Polish nationalism had also begun to surge around the same time, producing the anti-authoritarian Solidarity movement of the 1980s which helped bring down the USSR. Nationalism in Poland is no small thing. The Polish identity had survived one hundred twenty-three years of partition (from 1795 until the end of WWI in 1918), during which time Poland was completely erased from the map (the land was divided between Russia, Austria and Prussia). In fact, over the centuries, Poland has lost a great of land. In 1492, the Polish-Lithuanian Commonwealth was the largest territory in Europe. Today Poland is the ninth largest.

|

| Territorial changes of Poland from 1635 to 2009, Public Domain, Link |

It is not surprising that Polish nationalism was strong enough to withstand Soviet oppression. And yet, again, Poles never made an effort to reclaim that land. I am sure the displacement has always mattered, but not enough to fight over.

In contrast, there is great discontent in Israel and Palestine. Jews and Muslims in the Middle East have never had a chance for peace. Still, there is a huge asymmetry in their attitudes and positions. While 700,000 Arabs were displaced from Israel in 1947, around 900,000 Jews were displaced from Muslim countries in Africa and the Middle East after WWII. Yet there has never been a widespread effort to remove any of those Muslim countries from the map. The vast majority of what was once the Ottoman Empire remains Arab and Muslim, and there has been no effort or desire to change that. One small part of that fallen empire is now a Jewish state--the only Jewish state in the world, built in and around Jewish historic holy lands, built in part by Jews who have always lived on those lands, with a national and ethnic lineage that traces back thousands of years. And that Jewish state remains the only democracy in the Middle East. Yet there are millions of people all over the world, Muslim and not, Arab and not, who think it should not exist, and that its very existence is a catastrophe of the greatest proportions.

It does make me wonder.

*Much of my commentary on the history of Palestine is drawn from Western Imperialism in the Middle East 1914-1958, by D. K. Fieldhouse.

Comments